Description

This report analyses the progression of workers from process workers to supervisors in the oil and gas (hydrocarbons) industry, and the kind of training and work experiences they have undertaken. It also looks for commonalities in the skills progression for different workers, and draws out implications for the oil and gas industry, other industries and the vocational education and training (VET) system. The extensive formal and informal training delivered within the oil and gas industry has essentially been conducted in isolation from the formal VET sector. The study offers insights into the way advanced skills are developed by mature workers in a demanding industry, and suggests ways in which the VET sector could respond.

Summary

About the research

Global industries such as the oil and gas industry understand the value of training and do not need to be convinced to conduct training or to train more. Lack of engagement with the formal vocational education and training (VET) sector is not necessarily a sign that these industries disdain training: the oil and gas industry spends many millions of dollars annually on training. Lack of engagement with the sector, however, may be a signal the sector might reflect on.

- Workers' attitudes are key in developing a high performance/high skill workforce. Commitment to safety, a willingness to question and to learn are attitudes required to be recruited to the oil and gas industry. They are non-negotiable. VET providers working with candidates at entry level need to understand that developing appropriate attitudes in students is as important as their acquiring specialist skill and knowledge. This adds a considerable challenge to the training task.

- Competencies are more important than qualifications in the oil and gas industry because, when it comes to assigning work, competencies are the only currency. Qualifications on their own are insufficiently informative—a view shared by employees and employers.

- Skilled workers are different from entry-level learners in that, on the whole, they are far more confident learners and, in this industry, thrive on challenge. In a workplace that affords them the opportunities, they effectively take charge of their own learning program; they act like the autonomous professionals they are. This is a reminder that VET produces professional workers in the true sense of the word.

- Advanced skill learners reported requiring training with 'bite'. This means training where, to quote Dewey, people learn by doing, 'but the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking'. This requires thoughtful instructional design where the trainer perceptively judges the degree of challenge ('bite') in light of each worker's capacity to meet the challenge.

- There is a market for assessment and recognition of competencies. The 'safety case' regime, which identifies major risks in a facility and outlines ways of avoiding them or dealing with them should they occur, is now in effect in the oil and gas industry. This means that evidence of workers' skill and applicable knowledge must effectively meet a legal standard, which requires expert assessment of competencies. The VET 'recognition system' (where recognition of competence is formally granted) is more important than the traditional TAFE 'training delivery system' in this industry, and is in urgent need of attention.

- The role of time in learning needs re-thinking. Extended and repeated experience appears to be a critical element in acquiring advanced skill. No one is suggesting a return to 'time-serving', but we need to better understand whether (or where) repeated practice does not stall progress but actually opens out new horizons and expertise.

- Developing advanced skills in global industries has implications for Australia's immigration policies. Experiential learning to master leading-edge skill requires the learner to work alongside an expert. In global industries such expertise often resides outside Australia yet it is exceedingly difficult to obtain permission to import experts to work here for specified periods, even though a demonstrable outcome is the growth of local capability.

- Enterprises ought to conceptualise the workplace as a learning environment as well as the site where products/services are created. Learning environments are characterised by the tasks people are given, the resources at their disposal to complete the tasks, and the support offered. Experience suggests that it is of real benefit for employers to envisage their workplaces in terms of this trio of learning 'affordances' and observe the quality of the learning that emerges.

Executive summary

This report explores ways existing workers develop advanced skills in a technically demanding industry. The underpinning rationale is that the ability to develop workforces operating at the leading edge of skill and knowledge is critical if Australian enterprises are to be globally competitive. It is also important to understand whether the policies and practices of the formal vocational education and training (VET) sector — which have, in recent years, emphasised entry-level training — are equally applicable to advancing the skills of already skilled workers employed in their industry of choice.

The oil and gas (hydrocarbons) industry was chosen as the technically demanding global industry for two principal reasons. Firstly, enterprises in the industry take training seriously. Large companies spend many millions of dollars each year on the capability of their workforces and even the smallest companies now regularly review and update their work practices. This training has, however, been dealt with as a private, even proprietary, matter. Thus the second reason for selecting the hydrocarbons industry: it has developed a new interest in connecting with the formal VET sector through its response to the Chemical, Hydrocarbons and Oil Refining Training Package PMA02.

Within the wide range of activities under the banner 'the oil and gas industry', the production phase was selected for special attention in this study. This phase includes extracting oil and gas from deep underground, often offshore; 'cleaning' and separating components; and loading these for transport. It is essentially a process operation and its advanced skill issues are likely to be congruent with those of other industries (from food to power generation). It is also the area where assessment of workersí skills and knowledge is required to reach a legal standard in line with the 'safety case' regime now in place. This regime identifies major risks in a facility and outlines the measures needed to avoid these risks or cope with them should an incident occur. It also commits organisations to ongoing and detailed evaluation of safety and emergency management procedures, as well as more general competencies of workers carrying out assigned tasks.

Acquisition of advanced skills

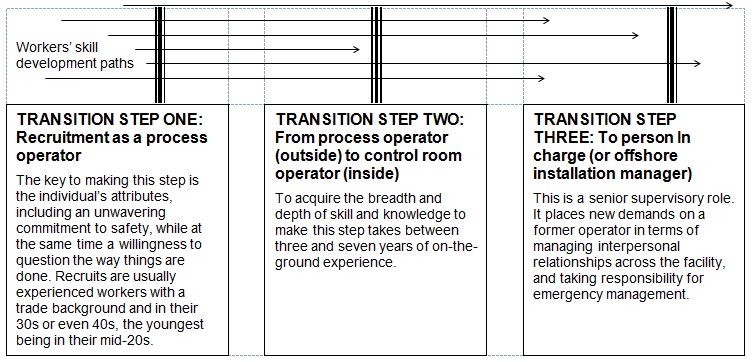

Identifying critical steps along the path to leading-edge skill was key to this study. Figure 1 illustrates the concept and describes the three skill transition points chosen to be the most instructive. The selection was made in consultation with industry: the study team interviewed 50 individuals from 27 organisations and enterprises, many of these more than once.

From a training point of view, the most revealing step concerning skill advancement was the second transition point — operators' gradual accumulation of expertise in the years between recruitment and permanently stepping into the control room. This is fundamentally a story of acquiring expertise through experiential learning and provides some insight into that elusive phenomenon.

Figure 1: Critical steps to leading-edge skill

Two potential misconceptions about this journey need to be eliminated at the start. Firstly, technical difficulty is not a significant barrier to learning; much of the knowledge and skill developed during the period is technically sophisticated but not so difficult as to block progress. Secondly, the difference between an operator taking three years or seven to gain this expertise appears to be a matter of personal inclination and cannot be seen as a failure of learning on the part of the employee, nor of teaching on the part of the employer.

Factors which enable operators to develop advanced skills through work include:

- Expectation: Operators are told at recruitment stage that they have been chosen explicitly and precisely because they were perceived to have both the aptitude and attitude to master the technical (and other) demands of the skill trajectory.

- Challenge: Operators recognise and appreciate high-quality, challenging training. On the other hand, they were scathing about what was considered boring, going-through-the-motions training. From their stories, it is clear that what quality training delivers is 'flow' in Csikszentmihalyiís (1990) sense; that is, a balance between degree of challenge and the person's (ultimate) capability to meet the challenge, so he or she is not only stretched, but finds the process fully absorbing.

- Continuity of practice: A common theme in the interviews was the importance of operators asking questions — questioning what they are doing, and what they see others around them doing. The extensive skills and knowledge gradually acquired in this way is, in their words, a 'more and more' process. The workplace gives them the opportunity to work at more and more tasks in more and more areas so they can find more and more questions to ask.For process operators the expertise, once acquired, seems reasonably fixed since they find they can take up where they left off when they return to the industry, even after a lapse of several years. This is not the case with drilling or the coded welding required during construction. In those cases, skill levels deteriorate if not continually honed.

- Targeted training: The importance of operators picking up skills by 'looking around' should not be taken to imply that formal training in technically difficult areas is unimportant or ignored. Experts are regularly flown in for a specific purpose; vendors instruct workers on the finer aspects of using their equipment; many operators recruited for a new installation spend time with the company designing and building the facility; sophisticated simulation programs are available; and so on.

The simple conclusion is that steady progress towards expertise in leading-edge skills depends on the fit between the opportunities for learning provided by the enterprise (affordances), and the motivation of the workers to pick up on the opportunities (engagement). What is critical is enterprises being alert to, and sophisticated about, creating workplaces which by their very nature are conducive to learning. This was concisely described in an interview conducted some time ago:

Employers need to be told: 'you might think you are managing a business — well, you are managing a business — but you are also managing a learning environment, whether you like it or not, thatís what you do: manage a learning environment! (Figgis consultation 2002)

A scheme for analysing the ways in which a particular workplace is, or is not, conducive to learning is described in this report (see table 2, which describes learning-conducive conditions of work). It is recommended that enterprises experiment with this scheme and use their experience to help refine it.

Relationship to the formal VET sector

The extensive, high-quality formal and informal training delivered within the oil and gas industry has essentially been conducted in isolation from the formal VET sector. A possibility for bridging that divide has opened up with the industry's interest in the Training Package PMA02. The oil and gas industry has shown particular interest in the package's well-defined process operation competencies, and its new incident response and emergency management competencies (which have not been available in such a systematic and rigorous form before). There are also two weaknesses in the industry's present skill development program: the underlying science in process operation is not widely understood; and supervisory skill (and mentoring skill) is left too much to chance. At entry level, a new industry-wide apprenticeship scheme was inaugurated in 2004 to counter anticipated shortages.

There are some clear lessons in this study for the formal VET sector—in particular, for public registered training organisations and policy-makers—if it is to capitalise on current opportunities to engage with the oil and gas industry. These lessons are:

- Competencies, not qualifications, are what enterprises in this industry care about both in recruiting and advancing their workforces. Similarly, the existing workers in this study are not interested in qualifications per se, but view them as a nice extra when offered.

- There is a pronounced difference between advancing the skills of already skilled workers and developing entry-level skills. This has not received much formal attention in VET literature. For the skilled workers in this study (compared with entry-level learners), the difference lies in both their positive motivation to learn and their confidence in their ability to learn. This affords their commitment to master a subject a resilience which less advanced learners often lack.

- Attitude and temperament provide the foundation on which skill development is built. If the formal VET sector is to meet industry needs, it must help potential workers to develop appropriate attitudes, especially attitudes such as eagerness to learn, vigilance about safety, and curiosity. These are not taught by reciting theory, but by using educational practices which encourage and reinforce the attributes, and by modelling.

- Both attitude and temperament lie largely outside the province of education and training. However, it is incumbent on VET practitioners that they understand the subtleties and paradoxes in the attributes required in a demanding industry at the advanced skill level. Workers need to be cautious and comfortable working in a risky environment; they need to adhere strictly to procedures and question the ways things are done; they need to be independent thinkers and cooperative team members. Discussion about 'generic skills' seems to miss this point.

- The industry does not need a campaign about the value of training. Enterprises already want training products and services of the highest quality, delivered with 'bite', and adapted to meet their needs.

For training at the advanced skills end of the spectrum, the technical equipment and expertise required are likely to exceed the resources of most non-enterprise-based registered training organisations. The solution is to develop partnerships where careful attention is given to the VET sectorís potential contribution. This is its pedagogical knowledge and experience; for example, skill in instructional design, the capacity to bring out the best in learners, and the provision of evidencebased assessment. The indications are that this is relevant to all technically demanding, globally competitive industries.